Climate for a Nation

Forecast: 1 January 1901

Climates of Opinion

Battling the Elements

Forecast: 1 January 2001

Endnotes

Index

Search

Help

Contact us

It was with considerable satisfaction that Littleton Groom rose to address the House of Representatives on 1 August 1906.[10] As the member for Darling Downs, Groom had been alarmed by the closure of the Queensland Weather Bureau in 1902, and had urged the Commonwealth to exercise its constitutional powers by establishing a Federal Bureau.[11] In the years that followed, Groom urged and urged again, taking the matter up with Prime Ministers Barton, Deakin and Watson.[12] But on 1 August 1906, he was no longer demanding action. As Minister for Home Affairs in the Deakin Protectionist government, it was Groom who finally introduced legislation to create a federal meteorological department.[13]

In his speech, Groom emphasised the value of accurate weather information for primary producers and shipping. National coordination offered improvements in efficiency and accuracy, but also, he noted, the opportunity for 'a proper study of climatic conditions . . . which are of importance in considering the suitability of certain localities for settlement and development'. 'Under a Federal system', Groom continued, 'we hope to become thoroughly acquainted with the climatic conditions of the continent'.[14] Groom wanted more than just efficiency; he imagined the Commonwealth Bureau as just one component in a system of institutions and legislation that would foster the settlement of Australia's 'empty spaces'.[15] Speaking on the Commonwealth takeover of the Northern Territory in 1909, Groom remarked: 'We are every year acquiring a better knowledge of our natural conditions and a better understanding of the laws of production'. Through the work of institutions such as the Bureau of Meteorology, Groom believed that 'much of the land that is now despised will ultimately become very productive'.[16]

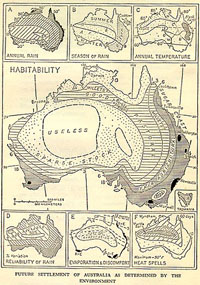

The Bureau's climatological research effort was bolstered when Griffith Taylor was appointed as 'physiographer' in 1910, although he promptly left for the Antarctic.[17] Upon his eventual return, Taylor subjected Australia's supposed 'potentialities' to scientific scrutiny, examining the effect of climate on settlement and the development of primary industries.[18] Australia was 'empty' for a reason, he concluded, the climate could not sustain the sort of intensive settlement that Groom and others had hoped for. Taylor's numerous publications on the topic were peppered with visually-arresting graphs and maps—climographs, hythergraphs, econographs, isoiketes—the tools of the meteorologist and the geologist were used to create a new kind of weather map, a forecast for the nation.[19] However, it was not a picture the nation builders expected or liked. The blanks on their map foretold opportunity, sunny skies over open plains; but Taylor's map forecast little change, a large, leaden mass had settled over the heart of the continent.[20] It was 'useless'.

Taylor's Australia was beset with deserts both climatic and cultural.[21] He was impatient with wilful ignorance and political posturing, and took as his mission to 'tell the truth and shame the booster'.[22] But he could also be arrogant and dogmatic, seeking to enshrine his own discipline at the core of the nation-planning exercise. For their part, the 'boosters' fell back on outraged expostulations, ridiculing 'armchair experts', and invoking the manly virtues of courage and determination as a match for any supposed climatic limits.[23] But they were hardly as irrational or ignorant as Taylor may have imagined. Taylor's critics were surveying a human landscape, seeking a role for the individual in the destiny of a nation. The distance between the two sides was not so great, and had the debate centred on small-scale, regional assessments, they may have found considerable room for agreement.[24] Instead there was a battle of the maps, as each side sought to trace the boundaries of nationhood on the outlines of a continent.

Even though Griffith Taylor fled the country in 1928, his assessments gathered authority and acceptance, particularly amongst the ranks of 'experts' and 'planners'. But the burgeoning power of science and technology also offered inspiration to the dreamers. New waves of optimism washed over the desert lands, hope sprouting afresh. In 1941, as Australians began to wonder about the shape of the postwar world, one of the country's most eminent engineers presented a plan to remake the continent. J. J. C. Bradfield, the designer of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, advocated a massive system of dams and tunnels to turn water from north Queensland rivers inland, ultimately to fill Lake Eyre.[25] The huge increase in surface water, he argued, would increase rainfall, permanently altering the climate of inland Australia.

Bradfield based his climatic theories on the work of E. T. Quayle, one of the Bureau's pioneer researchers and Griffith Taylor's former room-mate.[26] However, the new generation of meteorological researchers questioned Quayle's findings and dismissed Bradfield's extravagant predictions.[27] Only Quayle, now retired, offered any support. 'Having . . . satisfied myself that it is possible by human agency to bring about very considerable local improvements in the climate of the southern half of our continent', Quayle maintained, 'I am loath to believe that nothing of a similar character is likely to result in the northern half'.[28] But what government was likely to spend £30,000,000 to find out?[29]

Bradfield's dream may have seemed too ambitious, but another large-scale water diversion project became the symbol of Australia's postwar development. The Snowy Scheme combined traditional values of community and hard work, with a new sense of technological potency. Rivers and mountains could now be tamed, perhaps the weather itself would soon succumb. In a world where the boundary between energy and matter could be crossed at will, what limits could remain?

Griffith Taylor returned to Australia in the 1950s, in time to observe a new swell in the rhetoric of 'Australia Unlimited'.[30] In his morning newspaper he could read the head of CSIRO, Ian Clunies Ross, describing how 'poor, almost worthless soil' was being transformed into 'fertile pasture'; how exciting 'new possibilities' had emerged in the development of the north; and how rain-making experiments offered the prospect of 'substantially increased' rainfall. In words to gladden the heart of any 'booster', Clunies Ross proclaimed that 'there are no problems so great that they cannot be solved once we marshal our resources for a resolute and sustained attack on them'.[31]

The Australian national optimism index continues to swing between the highs of 'possibilism' and the lows of 'determinism'. Even as we ponder the environmental costs of the Snowy Scheme, we revel in nostalgia for its nation building heroics. In 2000, the outgoing president of the Australian Institute of Geoscientists called for an 'audacious water scheme' to permanently fill Lake Eyre, thus to increase rainfall across the Murray-Darling Basin. Such a project, he argued, 'could be a catalyst for uniting and inspiring us'.[32] Some politicians agree. 'In the past, ideas such as the Bradfield scheme have been dismissed as being unworkable,' commented the Labor member for Dunkley in 1993, 'But it has been proved that things which were considered impossible and impractical yesterday, are not so today through modern science and technology'.[33] The Liberal member for Dickson called for 'the determination to look at these things and make them happen'. He envisaged a new Snowy scheme, a program of major capital works that would 'end this terrible drought-wet cycle . . . and provide a vision for this country'.[34]

Edmund Barton rallied the Federation movement with the cry 'a nation for a continent, a continent for a nation', but the fit between nation and continent is still uncomfortable (perhaps a few tucks here . . . or a little off the length . . . ). Even with our supposedly heightened environmental sensibilities, each new flood or drought awakens the nagging suspicion that the weather is somehow against us. We have inherited a 'vision' of nation building that imagines its fulfilment in defeat of climate, the conquest of nature.

People in Bright Sparcs - Clunies Ross, Ian; Taylor, Thomas Griffith

|

Bureau of Meteorology |  |

© Online Edition Australian Science and Technology Heritage Centre and Bureau of Meteorology 2001

Published by Australian Science and Technology Heritage Centre, using the Web Academic Resource Publisher

http://www.austehc.unimelb.edu.au/fam/0003.html